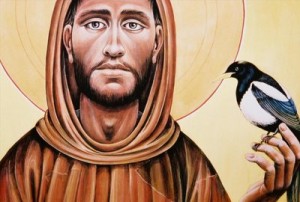

From June 6-7, a number of men from Central Baptist Church, North Little Rock, spent time in a retreat at Subiaco Abbey in Subiaco, Arkansas. This was the first of what I intend to be annual “Mighty Men of God” retreats in which men consider the lives of great men from Christian history. This year we considered the life of Francis of Assisi and what his example can show us about what it means to follow Jesus. To that end, I put together a workbook highlighting four episodes from Francis’ life. I am providing the Leader’s Guide of the workbook here, as a pdf. I hope it encourages and challenges you.

From June 6-7, a number of men from Central Baptist Church, North Little Rock, spent time in a retreat at Subiaco Abbey in Subiaco, Arkansas. This was the first of what I intend to be annual “Mighty Men of God” retreats in which men consider the lives of great men from Christian history. This year we considered the life of Francis of Assisi and what his example can show us about what it means to follow Jesus. To that end, I put together a workbook highlighting four episodes from Francis’ life. I am providing the Leader’s Guide of the workbook here, as a pdf. I hope it encourages and challenges you.

Tag Archives: biography

Augustine Thompson’s Francis of Assisi: A New Biography

In Francis of Assisi: A New Biography, Dominican friar Augustine Thompson has set out to offer a biography of St. Francis free of the mythological encrustations that inevitably latch onto figures of Francis’ spiritual stature. When I first read that this was Thompson’s stated purpose, I grew very cautious. This is not because I do not agree with a myth-free Francis. On the contrary, I am very much in favor of such because (a) I believe we ultimately do a disservice to our heroes when we romaticize them and (b) because the undeniably historical aspects of Francis’ life are in and of themselves so astounding that they should render the desire for attractive glosses undesireable anyway (and, of course, such glosses are always inappropriate, if still understandable). No, my concern was that Thompson’s modus operandiwould be a cover under which he would apply extreme skepticism and reductionism to the life of the beloved Francis.

I was pleasantly surprised to discover that Thompson is no unjust skeptic. In fact, I believe he has produced one of the stronger Francis biographies out today. His approach is sober but respectful. While he does not allow sacred and beloved myths about Francis to go unchallenged, neither does he lapse into mere incredulity just because a particular instance in Francis’ life seems surprising or even unlikely. Case in point would be Thompson’s handling of Francis’ alleged stigmata. His approach is respectful, if cautious. Ultimately, he finds no reason for doubting that something very odd and very physical happened to Francis, and he dismisses skeptics who dismiss the stigmata simply because they find the idea offputting.

Thompson tells Francis’ basic biography very well. He handles the wider political and ecclesiastical realities surrounding Francis adeptly and in a helpful manner. I felt that Thompson really shined in his examination of the innder dynamics of the growing Franciscan movement. Furthermore, I feel like I learned a good bit about the awkwardness surrounding Francis’ desire to be a “lesser brother” to his fellow monks. He wanted to be subservient, but, in practice, this proved very difficult given Francis’ stature as the founder of the movement.

Thompson has presented a very human portrait of Francis, and I enjoyed it very much. I believe he achieved his goal of historical accuracy. However, he clearly respects his subject and never lapsed into crass dismissiveness simply because many of the events surrounding Francis’ life were remarkable.

After all, Francis was a remarkable man…though Francis, no doubt, would respond, “No, but I have a remarkable God.”

And, of course, he would be right.

Michael Coren’s Gilbert: The Man Who Was G.K. Chesterton

My first encounter with G.K. Chesterton created quite a problem for me. I first read him in the midst of what I can only call a myopic fascination with and nearly obsessive reading of the works of C.S. Lewis in high school and college. In fact, my initial reading of Chesterton was due to Lewis’ own frequent reference to him and, in that sense, was a kind of corollary extension of the Lewis mania of which I was a willing and joyful victim. So it was that I picked up Chesterton’s Orthodoxy, though Lewis himself seemed more fond of his The Everlasting Man.

The problem I encountered when reading Orthodoxy was that it deeply challenged my own relatively recent (at the time) conviction of the seminal supremacy of Lewis’ Mere Christianity. Clearly, I am using “problem” here with no small measure of tongue-in-cheek, but I do remember experiencing an acute kind of spiritual sensory overload upon reading Chesterton for the first time. I found myself thinking thoughts that were utterly unthinkable to me at that time. Scandalous thoughts like, “I think Orthodoxy may actually be more poignant than Mere Christianity.” Or, “I think, if I am honest with myself, that I frankly enjoy reading Chesterton more than Lewis.”

I suspect the significance of this (and, of course, it is only significant to my own journey, but it is insignificant in every other conceivable way) can only be understood if I stress how blatantly life-changing, worldview-changing, spiritually-challenging, and path-altering Mere Christianity and the Lewis canon were and are to me. I know that my experience with Lewis and his work was no greater than the myriad similar testimonies of those whose paths and thinking were altered by Lewis’ writings, but I daresay that it wasn’t less. This is, of course, another post for another day, but I will say that Lewis’ work fell on the heart and mind and eyes and ears of a young fundamentalist Baptist with as much intensity, heat, and, if you will allow it, damage as any literary bomb that ever fell on any unsuspecting soul.

When I say, then, that the thought of Chesterton being superior to Lewis was scandalous to my own mind, you must believe that I mean precisely that. It felt almost like a betrayal, except for my being assuaged by the realization that Lewis would have wholeheartedly agreed with the assessment. I should also say that though I would likely claim (I still struggle here) that Chesterton is, overall, more edifying and enjoyable to read than Lewis, I rather suspect that Lewis’ genius was more thoroughly consistent and, in a sense, more spiritually sober in terms of its overall impact. But even here I waver.

I realize that may not make sense, but I truly do not care. If George Bernard Shaw could name the tandem of G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc “The Chester-Belloc,” surely I can be allowed to express my appreciation for “The Chester-Lewis.” Certainly, in my own experience, no two writers have so affected me as these two.

Why the attraction to Chesterton? I’m always trying to flesh this out, but I think, for me, above all else, I am most deeply touched by Chesterton’s celebration of paradox, his uncanny demonstration of common sense, and his almost casual but always penetrating evaluations (and often dismissal) of philosophies and ideologies that take themselves too seriously indeed. Of course, there is also Chesterton’s deeply contagious sense of joy and wonder, his childlike perception of the sheer miracle of existence. Chesterton’s writings (and Chesterton himself) are a wonderful tonic to the malady of societal insanity to which we have all been exposed and with which, to some extent, we have all been affected.

In 2003, Roni and I traveled with one of my Doctor of Ministry seminars to England where we spent two weeks completing our course on sight at Cambridge, Oxford, and other locales. (Please note: I do not claim that I “studied at Oxford” and find that way of describing the experience misleading. I say this for personal reasons. I would just assume that my peers refrain from saying the same. We did study, and it was at the locale of Oxford and Cambridge, and it occasionally involved meetings with some of their faculty ((like Bruce Winter)), but that is all. Forgive this idiosyncratic digression, but I have my reasons.)

While on this trip, in a bookstore in Stratford, England, I picked up Michael Coren’s 1989 Gilbert: The Man Who Was G.K. Chesterton. I have only just read it on our recent trip to the 2011 gathering of the Southern Baptist Convention meeting in Phoenix, Arizona. I do suspect that Chesterton would have found that fact amusing.

The biography is a solid, often very enjoyable, occasionally mildly frustrating, and seldom uninteresting look at a man who was larger than life in many ways. Coren tells the story with aplomb, and I had difficulty putting it down.

Coren offers personal insights and evaluations that stop short of tabloid peering. He is honest about Chesterton’s weaknesses without lapsing into vitriol and charitable with Chesterton as a man without lapsing into hero-worship. In this very helpful biography, Coren situates Chesterton squarely in his own day while acknowledging his continuing impact on the many who still turn to his work.

Coren provides some fascinating insights into the story of Chesterton’s marriage to Frances, his finances, his often surreal but usually charming personal quirks, his literary output, his many significant relationships, his political views, and his spiritual journey. I was struck by the interesting dynamics between Chesterton’s friends and the influence of his wife (which, in some ways, mirrored the reaction of C.S. Lewis’ friends to his wife, Joy.)

I do wish he would have spent a bit more time exploring the reactions and receptions of some of Chesterton’s major works, particularly Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man, but it is likely difficult to keep a biography at a managable length if one comments to any significant degree on such a prodigious literary output.

In all, Coren’s biography is helpful, substantive, balanced, and informative. I certainly do feel that I have an overall better grasp of GKC the man than I did before reading the biography.

I do think everybody should have some acquaintance with Chesterton. He is, regrettably, not to everybody’s taste. (One of my dearest friends found Orthodoxy virtually unreadable! Though I can’t conceive of how such a thing is possible, it apparently is.) Others, particularly Baptist readers, may find Chesterton’s Catholicism difficult to handle. I, for one, never fail to learn from Chesterton, even when I disagree with this or that position he might hold.

This is a really good biography of a really great man.

Paul Brewster’s Andrew Fuller: Model Pastor-Theologian

My Thanksgiving-break book this year was Paul Brewster’s fascinating Andrew Fuller: Model Pastor-Theologian, a selection in B&H’s “Studies In Baptist Life and Thought” series. Fuller’s is a name you encounter increasingly these days (as evidenced, for instance, by “The Works of Andrew Fuller Project”and “The Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies”), and those familiar with the theological, ecclesial, and denominational frictions within the Southern Baptist Convention will understand why.

Andrew Fuller was a British Baptist pastor and theologian (largely self-taught) who exerted a marked influence over the Baptist church which he pastored and the association of which he was an important part. (As an aside, Brewster’s description of the heightened collegiality of British associationalism was quite insightful). So great was his influence, that one historian claimed he achieved a kind of de facto bishopric in the area. His was a ministry characterized by great fruit and great controversy, the latter likely being the reason for the renewed interest in Fuller today.

Andrew Fuller was a British Baptist pastor and theologian (largely self-taught) who exerted a marked influence over the Baptist church which he pastored and the association of which he was an important part. (As an aside, Brewster’s description of the heightened collegiality of British associationalism was quite insightful). So great was his influence, that one historian claimed he achieved a kind of de facto bishopric in the area. His was a ministry characterized by great fruit and great controversy, the latter likely being the reason for the renewed interest in Fuller today.

Essentially, Andrew Fuller pushed back against the “High Calvinism” (read, “hyper-Calvinism”) of John Brine and John Gill. I do understand that the contention that Gill was “hyper” in his Calvinism is hotly disputed. It is possible that Brine’s presentation of Gill’s thought gave rise to the assumption. It is also possible that Gill was, in fact, a hyper-Calvinist. I’ll leave that to others to decide.

The hyper-Calvinism of Fuller’s day had essentially suffocated evangelistic efforts among 18th century British Baptists. Gospel appeals to the lost were expressly avoided unless a lost person gave some evidence of a “warrant,” or indication that they might be among the elect. As such, evangelism suffered and evangelistic means were avoided.

It must be understood that Andrew Fuller did not break with Calvinism per se, he broke with hyper-Calvinism. Fuller nuanced his Calvinism into a kind of evangelistic, missionary Calvinism. He did not reject election. He simply rejected the notion that a warrant must be present to justify evangelistic outreach. Fuller argued that, on this side of Heaven, we do not know who the elect are. As such, we should hear the missionary impulse within scripture and indiscriminately offer the gospel to all people in all nations. It is hard for us to imagine this being controversial, but it was in his day and context.

Fuller also nuanced his approach to limited atonement, arguing that while the atonement was efficient only for the elect, it was sufficient for the sins of the whole world. As such, we may yet again feel not only the freedom, but the imperative of preaching Christ to all people, everywhere, under the biblical assumption that the blood of Christ is a sufficient payment for the sins of the world.

Fuller is also notable for his efforts (alongside William Carey) in beginning the Baptist Missionary Society, which constitutes, essentially, the beginning of the modern missionary movement. Fuller was the society’s head at home, working tirelessly to handle the various organizational, financial, and logistical issues that arose in the execution of this important ministry. He was, in Carey’s famous terminology, the one who “held the rope” for the missionaries while they went to the field.

Fuller is also notable for his efforts (alongside William Carey) in beginning the Baptist Missionary Society, which constitutes, essentially, the beginning of the modern missionary movement. Fuller was the society’s head at home, working tirelessly to handle the various organizational, financial, and logistical issues that arose in the execution of this important ministry. He was, in Carey’s famous terminology, the one who “held the rope” for the missionaries while they went to the field.

Brewster reveals that some believe Fuller to have been under-appreciated in his role in the formation of the Baptist Missionary Society. Others seem to overstate Fuller’s importance. To be sure, William Carey’s name is rightly synonymous with the founding of the modern missionary movement, but it is only right to recognize as well the enormous role that Fuller played. To use Carey’s terminology, what would become of those descending below if those holding the rope were not faithful? And, by all accounts, Fuller was a faithful “rope holder,” almost obsessively so.

The current revival of interest in Fuller may be attributed in part (as Brewster recognizes) to the controversies surrounding Calvinism in the Convention today. It is a controversy I’m disinterested in commenting on here. Regardless, Fuller represents a possible via media in the modern controversy, showing the one side that (a) not all Calvinism is hyper-Calvinism and (b) that Calvinism in and of itself is not inherently inimical to fervent evangelism, and showing the other side that an imbalanced preoccupation with the Calvinist system, untempered by those significant portions of scripture that speak of and illustrate the worldwide missionary impulse of the early church and need to take the gospel to the nations can lead to a stifling of missions and evangelism.

A man like Andrew Fuller, and his example of passionate evangelism and missions, may serve to help temper the unfortunate rancor of the modern situation in the SBC. To put it mildly, were the Convention populated by people as passionate about preaching the gospel of Christ to the nations as Andrew Fuller was, we may would just see revival break out in earnest in our day.

I was also challenged by this book’s depiction of Fuller’s approach to pastoral ministry. Fuller was quite scrupulous about the need for him to be an undershepherd to the people of God. He worked tirelessly in knowing and reaching his people, and those outside of his own church. Fuller never seemed to coast in his pastoral duties, even though, at times, his work in the missionary society caused him to do less than he likely should have for his own people.

In all, this is a truly wonderful and insightful biography. It’s well-written (if a tad repetitious at times) and engaging. I suspect that anybody could read it to great profit.

Paul Maier’s Martin Luther: A Man Who Changed the World

Some Lutheran friends who attend our church gave me this wonderful little children’s biography of Martin Luther a couple of weeks ago. It’s little in terms of pages, but it’s actually an oversized coffee-table type book with tremendous illustrations by artist Greg Copeland. After reading it through I gave it the ultimate test by having my 10-year-old daughter read it through and then answer a few questions I posed to her. After hearing her say, “Saint Anne, help me! I will become a monk!”, I was convinced that this book is, in fact, a very effective tool for introducing children to Luther.

There are qualms, of course, as there are bound to be with any brief work that treats such a large topic. For instance, I regret Maier’s observation that the clergy of Luther’s day were corrupt. To be sure, there was widespread corruption, but the implication that all the clergy were wicked is unfortunate and could have been remedied by adding the words “many of the” before the word “clergy.”

That being said, how exactly is one to avoid oversimplification with a book like this?

All in all, a tremendous work and a great way to introduce kids to Reformation history.

D.M. Thomas’ Solzhenitsyn: A Century in His Life

Through current authors such as Os Guinness and Chuck Colson, interest in Solzhenitsyn continues to be cultivated in Evangelical circles. Interestingly, one may walk into any Family Christian Store and find the latest biography on Solzhenitsyn written by Roman Catholic author Joseph Pearce, a sign of his abiding influence. Truly, he is a man worthy of our consideration and, I would say, appreciation.

That being said, Thomas’s biography will disturb many Christians who perhaps have a white-washed view of Solzhenitsyn. While Thomas’s work has an overall laudatory tone about it, he does not shy away from Solzhenitsyn’s dark side: his affair and subsequent marriage to his mistress (his current wife), his harshness in dealing with those around him, his insensitivity to his first wife, and his temper. Yet he also highlights Solzhenitsyn’s strengths: his conversion to Christianity in the Russian Gulag, his ideological honesty, his dogged determination, his brilliant and fearless condemnation of Communism and Western materialism, his stringent and massively productive work schedule, and his genuine care over the fate of the world. What readers are left with is a picture of a deeply flawed and deeply determined man.

I am glad I read this book. In addition to having a more balanced understanding of this paradox of a man, I have a renewed appreciation of the fact that God uses broken vessels. There is much in Solzhenitsyn that is lamentable. There is much worthy of emulation. Read this book carefully and cautiously. You will be moved deeply by this story.

G.R. Evans’ John Wyclif: Myth & Reality

“Wyclif,” writes G.R. Evans at the end of the Preface to her John Wyclif: Myth & Reality, “may not be lovable, but he deserves sympathy and a kind of respect. What kind, and for what, the reader may judge from the following pages” (p.11). Based on the pages that follow her Preface, I would say that the respect Evans appears to think Wyclif deserves is minimal at best. Two-hundred-and-forty-five pages later, Evans concludes her biography with this: “History gains rather than loses when it becomes possible to treat a hero as a complex and fallible human being, with all the dimensions which enrich as much as they challenge the earlier, simpler pictures of the man who was hero and villain” (p.256). True enough. Balance is important. It’s unfortunate that this book didn’t seem to have much.

Let me stop before I’m guilty of being as unfair to Evans as she occasionally appears to be to Wyclif. The book is very well written, even if it is fairly tedious at times. The problem seems to be the scant biographical evidence that actually exists on Wyclif, at least the kind of interesting and anecdotal personal information that has become the staple of the genre in modern times. This is, in fact, a historical and intellectual biography of the enigmatic figure that has been called (Evans believes naively) “The Morning Star of the Reformation.”

And, to be fair yet again, Evans does make her case very well that what biographical work has been done on Wyclif (and there has not been very much at all) has tended to be hagiographical. That’s common enough. Such romanticizing and glossing is common in John Foxe, for instance, as well as in the writings of those who wish to present the Reformation, and, in the case of Wyclif, its precursors as a monolithic movement of like-minded saints driven by pure conviction and principle.

Evans demonstrates that this is, indeed, naïve when it comes to Wyclif. Wyclif was an enigmatic figure: an Oxford intellectual who appears to have smarted about being passed over for career advancement in the heady intellectual, ecclesiastical, and civil crosscurrents that intersected in and around 14th century Oxford. Evans also demonstrates clearly enough that Wyclif was prone to brooding, bitterness, and anger.

I cannot help but believe, though, that Evans overplays her hand. Time and again we are told that Wyclif is bitter, that Wyclif is angry, that Wyclif seemed unable to pull himself out of a pit or resentment. When Wyclif returns to a favorite theme of his – that true religion is, as James said, caring for the orphan and widow – Evans opines that there’s no real evidence of any concrete philanthropic tendencies in Wyclif and that his appeal to this definition of true religion was more a polemic against the friars and religious orders he detested as being predatory and parasitic on the laity than an actual conviction that this was, in fact, the true nature of religion. In fact, Evans suggested that most of Wyclif’s positive assertions were probably, in fact, responses to his enemies and not so much positive convictions.

We are told that Wyclif’s views of Scripture really weren’t so revolutionary. There were plenty of others who wanted the Word to be made available to the people. Regardless, Evans assures us, it’s unlikely that Wyclif actually did any translation work himself anyway. We are told that he was a snobbish preacher, insulting the congregations he should be nurturing. We are told that he drove most or all of his friends away, that he was inconsistent in what he thought should be and in what he actually did. We are told that, in most respects, he was a typical medieval scholastic. We are told, in essence, that Wyclif was essentially a man of his times…which does seem odd indeed.

In short, I believe that Evans goes too far even while making an overall helpful contribution to Wyclif studies. Her appeal for biographical balance seems to lean towards the negative in ways that are disheartening. We do not need to naively gloss our heroes. And it’s probably true that Wyclif’s role as a pre-Reformer has been glossed in this way. But without Evans’ consistent meanderings that probably what Wyclif was actually writing and arguing was driven more by anger than conviction, we would probably see from the same raw data that Evans presents that Wyclif’s views were, in a very real sense, precursors to what would become the fully bloomed doctrines of the Reformation two hundred years later.

It seems to me an uncharitable way to do biography. But, you will learn a great (excruciating?) deal about the workings of Oxford as well as of Wyclif’s own views. You will get some fascinating insights into the tumultuous religious, political, and intellectual landscape of Wyclif’s day.

Was Wyclif “The Morning Star of the Reformation”? It’s a bit hard to say after reading Evans’ biography. He was an imperfect man, prone to fits of temper, but he did articulate Reformation tenets in a pre-Reformation era in ways that were compelling and admirable.