1 When morning came, all the chief priests and the elders of the people took counsel against Jesus to put him to death. 2 And they bound him and led him away and delivered him over to Pilate the governor.

11 Now Jesus stood before the governor, and the governor asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” Jesus said, “You have said so.” 12 But when he was accused by the chief priests and elders, he gave no answer. 13 Then Pilate said to him, “Do you not hear how many things they testify against you?” 14 But he gave him no answer, not even to a single charge, so that the governor was greatly amazed.

22 Pilate said to them, “Then what shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?” They all said, “Let him be crucified!” 23 And he said, “Why, what evil has he done?” But they shouted all the more, “Let him be crucified!” 24 So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.” 25 And all the people answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!” 26 Then he released for them Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, delivered him to be crucified.

Two days from now the Greek Orthodox Church will be honoring a rather unlikely saint: Pontius Pilate’s wife. The scriptures do paint her in a rather favorable light, so it is not that difficult to see her as good woman. However, I must say it is indeed surprising to see the Ethiopian Church venerating Pilate’s wife and Pontius Pilate every June 19. While this is quite surprising to a lot of us, it apparently would not have been so to many in the early Church.

In Jerry Ryan’s Commonweal article, “Saint Pontius Pilate?” he notes that many in the early Church viewed Pilate in a favorable light.

Early Christianity went easy on Pilate…Tertullian invokes Pilate as a witness to the death and resurrection of Christ and of the truth of Christianity—and explains that this is why he is mentioned in the Nicean Creed. St. Augustine saw Pilate as a prophet of the Kingdom of God (cf. sermon 201). Hippolytus draws a parallel between Pilate and Daniel—in so far as both proclaim themselves absolved from the shedding of innocent blood (Daniel 14:40). Other Church Fathers likened Pilate to the Magi, who also recognized Jesus as King of the Jews.[1]

As somebody who tries to be a student of Christian history, and who believes that we should dismiss the wisdom of the early Christians only with great care and after firmly establishing their error, I must say that I simply disagree with this. The picture of Pilate that emerges from the pages of the New Testament is not one that inspires appreciation, much less veneration. On the contrary, the picture that emerges of Pilate is one of a selfish, self-serving, and cowardly politician who tried to have his cake and eat it too.

Pilate rejected Jesus in order to safeguard his own life and career.

To be perfectly blunt about it, Pilate was looking out for one person: Pilate! Here is what our text reveals about him.

1 When morning came, all the chief priests and the elders of the people took counsel against Jesus to put him to death. 2 And they bound him and led him away and delivered him over to Pilate the governor.

11 Now Jesus stood before the governor, and the governor asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” Jesus said, “You have said so.” 12 But when he was accused by the chief priests and elders, he gave no answer. 13 Then Pilate said to him, “Do you not hear how many things they testify against you?” 14 But he gave him no answer, not even to a single charge, so that the governor was greatly amazed.

22 Pilate said to them, “Then what shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?” They all said, “Let him be crucified!” 23 And he said, “Why, what evil has he done?” But they shouted all the more, “Let him be crucified!” 24 So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd,

Pilate, seeing that he was losing control of the crowd, relented to their demands and handed Jesus over to be crucified. To understand why, you have to understand who Pilate was.

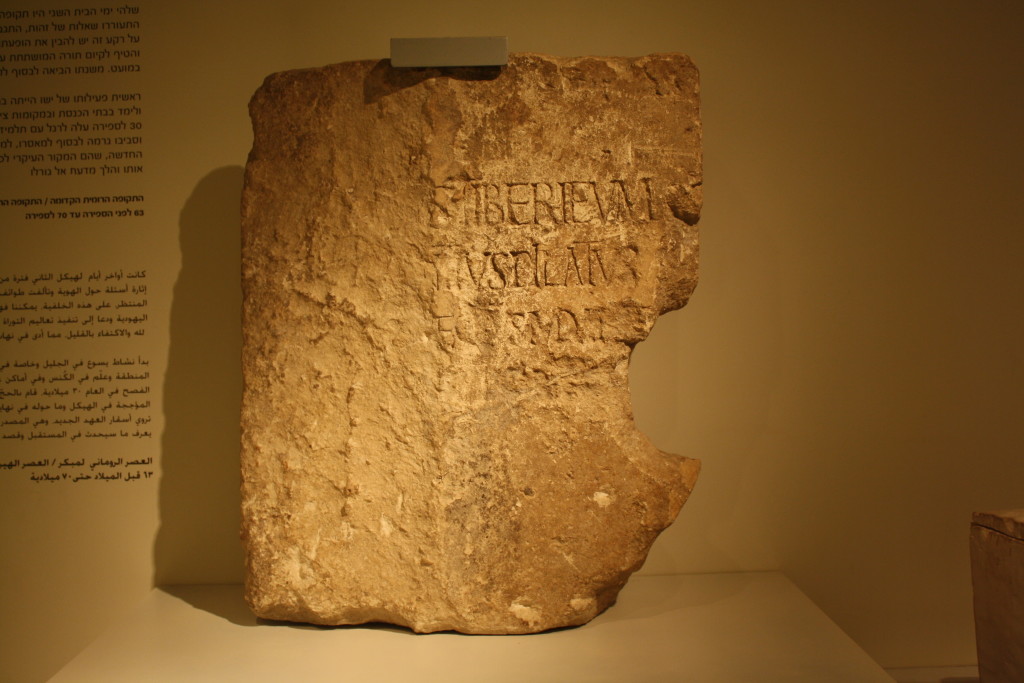

Until 1961, the primary evidence for the existence of Pontius Pilate was the New Testament record and a few scant references in later copies of Roman histories. Then, in 1961, archaeologists discovered “the Pilate Stone,” a limestone block with three lines of Latin carved into it.

Line One: TIBERIEUM

Line Two: (PON) TIUS

Line Three: (PRAEF) ECTUS IUDA (EAE)

William Barclay offers some insight into what kind of man he must have been.

Pilate was officially procurator of the province; and he was directly responsible, not to the Roman senate, but to the Roman Emperor. He must have been at least twenty-seven years of age, for that was the minimum age for entering on the office of procurator. He must have been a man of considerable experience, for there was a ladder of offices, including military command, up which a man must climb until he became qualified to become a governor. Pilate must have been a tried and tested soldier and administrator. He became procurator of Judaea in A.D. 26 and held office for ten years, until he was recalled from his post.[2]

Barclay has further outlined certain details of Pilate’s life and career that demonstrate the kind of man he was and the reason why the Jews despised him so very much. Among these details are the following:

- Every governor of Judaea before Pilate had removed the Roman insignia of the eagle in order to honor the Jews’ abhorrence of graven images. Pilate would not do so.

- When Pilate launched a major product to put a new aqueduct in Jerusalem to insure better water for the city, he paid for it with money from the Temple treasury.

- The Jews had threatened to report Pilate’s obstinacy and cruelty to the Emperor, a fact that galled him greatly.

- Pilate was recalled to Rome after he savagely butchered a group of Samaritans who had gathered at Mount Gerizim in Samaria to see a reputed messianic figure.

- Legend has it that Pilate committed suicide and his body was thrown into the Tiber River. However, his evil spirit agitated the waters so much that they pulled him out and threw him in the Rhone. After those waters were likewise agitated, he was buried in Lausanne.[3]

Again, the picture that emerges is not worthy of emulation. It is is worthy of disdain. Pilate knew that he was already on thin ice with Rome and that he likely would not survive another uprising. Thus, he did what was politically expedient and gave in to the unjust demands of the baying crowd. Even modern politicians see this in Pilate’s behavior. For instance, former Prime Minister Tony Blair admits to being intrigued by Pilate and said this about him:

[Pilate] commands our moral attention not because he is a bad man, but because he was so nearly a good man. One can imagine him agonising, seeing that Jesus had done nothing wrong, and wishing to release him. Just as easily, however, one can envisage his advisers telling him of the risks, warning him not to inflame public opinion. It is a timeless parable of political life.[4]

It is true that Pilate seems not to have had any personal animus toward Jesus. It is true that Pilate seems to have been intrigued by Jesus. It is likewise true that Pilate appears to have known that Jesus was innocent. But I ask you: do those facts make Pilates’ capitulation less or more shameful? Surely they make them more shameful.

Pilate was protecting Pilate…much as you and I are tempted to protect ourselves when following Jesus would cost us something. Is it not so? The subtle temptation to be silent instead of speaking up for the truth of the gospel is itself a Pilate temptation. The temptation to take the easy road just at that point where following Jesus would actually cost us something is a Pilate temptation.

Church, it costs to follow Jesus. It would have cost Pilate to do so, but it would have been the better way.

Pilate rejected Jesus though he attempted to say that he had not really done so.

Of course, Pilate, like us, was quick to justify his rejection as not really being a rejection. He even indulged in dramatic theater in an effort to distance himself from his own rejection.

24 So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.” 25 And all the people answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!” 26 Then he released for them Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, delivered him to be crucified.

“I am innocent of this man’s blood.” Would that it were that easy. Would that we could actually remove ourselves from culpability on the basis that, while, yes, we did reject Jesus, we nonetheless think very highly of him. It is no use saying that you personally saw nothing wrong in Jesus while you yourself turn Him over to the mob.

We try the very same thing. In numerous ways we try to say that our rejections are not actual rejections. We dress up our rejections in the language of cultural sensitivity or language about this not being “the right time” to bear witness to Christ. In truth, it seems that the most timid people in the modern world are Christians. But these timid avoidances of proclamation are as much rejections in the moment as was Pilate’s. They are as much an attempt to wash our hands clean of the charge of abandonment as was Pilate’s.

There is a an old legend stating that Pilate rises from his mountain grave and emerges every good Friday to wash his hands. The idea behind the legend is that this token effort at proclaiming innocence was shamefully inadequate and now is his eternal curse. We are known by our fruits, and, in the end, Jesus passes through Pilate’s hands to get to the cross. He cannot escape that.

This is why I object to the veneration of Pilate as some sort of saint. I am afraid if we canonize him as some have we will be canonizing one of the more absurd efforts at sidestepping the obvious in the history of the world. We will be canonizing the political dodge, the loophole, the, “Well, I always liked Jesus so it cannot really be said that I rejected Him per se.”

But that is exactly what it means, be it Pilate or us.

Pilate could have stood with Jesus. He was simply unwilling to pay the price for doing so.

As we prepare to approach the Lord’s Supper table, I would like to remind us of this fairly obvious fact: Pilate could have stood with Jesus.

He could have.

What would have happened if he would have refused to turn Jesus over, if he would have proclaimed his allegiance to Christ? At the least it would have been the end of his political career and it may have cost him his life. But he would have been standing with the King of Kings and Lord of Lords.

This text on Pilate is an unlikely communion text, but perhaps not as unlikely as we might think. After all, the table of the Lord calls us to a clear proclamation of what side we inhabit. Will we stand with Jesus or, like Pilate, will we reject Him and then try to say that it really was not a rejection at all? Will we take the cross, or will we choose the path of self-preservation? After all, the elements speak of a torn body and shed blood. It costs to follow Jesus. That is why we eat and drink.

This do in remembrance of Me.

To do in remembrance of Pilate is to look out for yourself. To do in remembrance of Jesus is to take the cross and follow Him.

We come to a table and think about flesh and blood, not about Roman thrones and upward mobility.

So here is the question: will you come to the table, or will you deny King Jesus? It does no good to say that your denials are not, in fact, denials. Of course they are. There really is no murky middle ground in which we are somewhat for Jesus and somewhat against Him. There is only a choice between Jesus or Pilate.

Which will you choose?

Which will you choose?

[1] https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/blog/saint-pontius-pilate

[2] William Barclay, Gospel of Matthew. Vol. 2. The Daily Study Bible (Edinburgh: The Saint Andrew Press, 1967), p.394-395.

[3] William Barclay, pp.395-397.

[4] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/personal-view/3556458/How-much-blood-is-on-Pontius-Pilates-hands.html