1 “If a man steals an ox or a sheep, and kills it or sells it, he shall repay five oxen for an ox, and four sheep for a sheep. 2 If a thief is found breaking in and is struck so that he dies, there shall be no bloodguilt for him, 3 but if the sun has risen on him, there shall be bloodguilt for him. He shall surely pay. If he has nothing, then he shall be sold for his theft. 4 If the stolen beast is found alive in his possession, whether it is an ox or a donkey or a sheep, he shall pay double. 5 “If a man causes a field or vineyard to be grazed over, or lets his beast loose and it feeds in another man’s field, he shall make restitution from the best in his own field and in his own vineyard. 6 “If fire breaks out and catches in thorns so that the stacked grain or the standing grain or the field is consumed, he who started the fire shall make full restitution. 7 “If a man gives to his neighbor money or goods to keep safe, and it is stolen from the man’s house, then, if the thief is found, he shall pay double. 8 If the thief is not found, the owner of the house shall come near to God to show whether or not he has put his hand to his neighbor’s property. 9 For every breach of trust, whether it is for an ox, for a donkey, for a sheep, for a cloak, or for any kind of lost thing, of which one says, ‘This is it,’ the case of both parties shall come before God. The one whom God condemns shall pay double to his neighbor. 10 “If a man gives to his neighbor a donkey or an ox or a sheep or any beast to keep safe, and it dies or is injured or is driven away, without anyone seeing it, 11 an oath by the Lord shall be between them both to see whether or not he has put his hand to his neighbor’s property. The owner shall accept the oath, and he shall not make restitution. 12 But if it is stolen from him, he shall make restitution to its owner. 13 If it is torn by beasts, let him bring it as evidence. He shall not make restitution for what has been torn. 14 “If a man borrows anything of his neighbor, and it is injured or dies, the owner not being with it, he shall make full restitution. 15 If the owner was with it, he shall not make restitution; if it was hired, it came for its hiring fee.

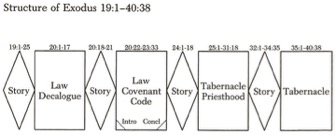

We are in a section of the book of Exodus that, at times, can feel a bit overwhelming with its legal codes and discussions of societal justice. Specifically, we are currently studying a section of the book of Exodus known as “the covenant codes” or “The Book of the Covenant.” In an effort to offer some perspective and context, let me show a diagram that was developed by Terence E. Fretheim.

Fretheim offers a number of reasons why this story-law-story-law-story structure is important. Among the reasons are these:

- “God is the subject in both law and narrative. God is the giver of the law and the chief actor in the narrative.”

- “Law is more clearly seen a gift of God’s graciousness when tied to story.”

- “Narrative keeps the personal character of the law front and center.”

- “This integration keeps divine action and human response closely related to each other.”

- “The motivation given for obedience to law is contained in the narrative: you were slaves in the land of Egypt, therefore you are to shape your lives toward the disadvantaged in ways both compassionate and just (22:21-17; 23:9).

- “Tradition has given the word Torah to both law and narrative genres. The force of this is that the Pentateuch is instruction…in both its laws and its stories.”[1]

Perhaps that is helpful. It shows us, when we are tempted to get frustrated with the details, many of the particulars of which are bound to a particular time and place, that there is a rhyme and reason for the structure of the book. Most significantly, the weaving of these law sections into the story do keep them from drifting into the merely theoretical or even the merely legal. On the contrary, these laws represent the gracious gift of God to an ancient people who needed to maintain a just societal order and life together just as we do today.

Our text is dealing specifically with the principle of private property and the right handling of it. Furthermore it outlines what should happen when this right is violated.

The right of private property should be honored and appropriate restitution should be paid when it is violated.

I am not, of course, trying to project our modern capitalistic society onto ancient Israel when I refer to “the right of private property.” Even so, wherever there are prohibitions against theft, there is an implicit acknowledgment of the rights of property owners not to have their property stolen by those who do not own it. It is easy to see how such a recognition is critical to maintaining social order, for if one may simply take whatever one wants from whomever one wants to steal from, chaos will soon ensue.

1 “If a man steals an ox or a sheep, and kills it or sells it, he shall repay five oxen for an ox, and four sheep for a sheep. 2 If a thief is found breaking in and is struck so that he dies, there shall be no bloodguilt for him, 3 but if the sun has risen on him, there shall be bloodguilt for him. He shall surely pay. If he has nothing, then he shall be sold for his theft.

If you steal an ox, you must repay five oxen. The text immediately preceding this sought to establish the principle of proportionate response in its articulation of lex talionis (“an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”). Even so, it is necessary to establish a reasonable deterrent for the stealing of property. After all, stealing an ox in an agrarian society is never merely stealing an ox. Rather, it is stealing the ox, diminishing the owner’s ability to complete as much work as he could with the ox, and, ultimately, taking food out of the mouths of the owner’s family as well as money from him if he sells some of his produce or hires the ox out for building or labor projects. In other words, to steal an ox is to threaten, in a very real way, the security of a family. Thus, if you steal an ox or a sheep, you must repay five oxen or four sheep.

Verse 2 and 3 suggests that a man may rightly protect his family from a thief breaking in at night. Verse 3, however, is very interesting and is somewhat difficult to interpret. William H.C. Propp of the University of California has proposed that the text can be interpreted either spatially (“the text might be differentiating between robbing an open-air enclosure as opposed to a roofed domicile”) or temporally (“it could be a simple day vs. night distinction”). If it is spatial, it could simply be saying that “a man breaking into a house may be presumed to be a murderer” but “a man breaking out has already shown his milder intentions.” If this is the correct interpretation, it would suggest that you cannot kill a man as he is fleeing your property, even if he has stolen. He obviously is not there to take a life.

Propp, however, argues for a temporal interpretation, which means that the text could refer to sunrise (“if a day has passed, then to kill the burglar would be a crime of cold blood not self-defense”) or it could mean “by day.” Propp explains:

Job 24:13-17 associates the nighttime with nefarious deeds in general, including housebreaking (vv 14,16)…It makes sense to be more cautious at night. By day, a thief might assume that a home is empty; at night, his assumption would be that it is occupied. Moreover, by night there can be no testimony as to the thief’s identity, nor can he be easily tracked…Decisive are the parallels from other cultures that permit a man to defend his property to the utmost – but only at night.[2]

There is wisdom here, though the wording of our text is perhaps too ambiguous for us to be dogmatic on any one of the proposed interpretations. Regardless, this much seems to be the case with any of these proposals: you cannot set up a mechanistic cause-and-effect scenario whereby you have the right to kill a person simply because he has broken into your home. It also seems clear that a person breaking in at night would seem to suggest at least the possibility of more nefarious motives, thereby justifying a more severe response, than would a person breaking in during the day or a person fleeing your house into the light of day. In offering this qualification, the right to protect one’s family is safeguarded while parameters are put into place to keep bloodshed from happening if it can be reasonably established that the thief is not there to kill those in the home.

4 If the stolen beast is found alive in his possession, whether it is an ox or a donkey or a sheep, he shall pay double. 5 “If a man causes a field or vineyard to be grazed over, or lets his beast loose and it feeds in another man’s field, he shall make restitution from the best in his own field and in his own vineyard. 6 “If fire breaks out and catches in thorns so that the stacked grain or the standing grain or the field is consumed, he who started the fire shall make full restitution.

Here again, appropriate restitution is required when the property of another is destroyed through either malevolent intent or carelessness.

It should be pointed out that there is another way that we can sin against one another through property. In the 6th century, Gregory the Great pointed out that it is also possible to be guilty of harming another by withholding one’s goods from those in need, a point on which, Gregory argued, the New Testament is actually more stringent than the Old.

Some people consider the commandments of the Old Testament stricter than those of the New, but they are deceived by a shortsighted interpretation. In the Old Testament, theft, not miserliness, is punished: wrongful taking of property is punished by fourfold restitution. In the New Testament the rich man is not censured for having taken away someone else’s property but for not having given away his own. He is not said to have forcibly wronged anyone but to have prided himself on what he received.[3]

Gregory was speaking of the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31), the former of whom went to hades when he died and the latter of whom went to Abraham’s bosom. In truth, he could also have been speaking of the rich young ruler (Mark 10:17-22), who only lacked one thing: to sell all he had and give it to the poor. In other words, it is sinful for a man to take what does not belong to him, but it can also be sinful for a man not to give what does belong to him if others are suffering without.

I would like to add that the story of history shows that governments seeking to force this kind of charity by simply confiscating all private property usually end up becoming monstrous and bloody entities of persecution themselves. The story of communism, for instance, is not a pretty story. Even so, most just societies see the need for some kind of reasonable regulations and protections for the poor. At its healthiest, what this looks like is the wealthy freely and generously giving to the poor, though history also shows that this does not happen as frequently as it should. Regardless, it should happen among the people of God.

The degree of guilt is justly less when the right of private property is unintentionally violated than when it is intentionally violated.

Laws need to be clear in a just society, but the circumstances to which laws apply oftentimes are anything but. For instance, it can and sometimes does happen that the property of another is destroyed either carelessly or accidentally. Such a situation is clearly different than a person who sets out with the intent to steal and take from another. Our text acknowledges this reality.

7 “If a man gives to his neighbor money or goods to keep safe, and it is stolen from the man’s house, then, if the thief is found, he shall pay double. 8 If the thief is not found, the owner of the house shall come near to God to show whether or not he has put his hand to his neighbor’s property. 9 For every breach of trust, whether it is for an ox, for a donkey, for a sheep, for a cloak, or for any kind of lost thing, of which one says, ‘This is it,’ the case of both parties shall come before God. The one whom God condemns shall pay double to his neighbor. 10 “If a man gives to his neighbor a donkey or an ox or a sheep or any beast to keep safe, and it dies or is injured or is driven away, without anyone seeing it, 11 an oath by the Lord shall be between them both to see whether or not he has put his hand to his neighbor’s property. The owner shall accept the oath, and he shall not make restitution. 12 But if it is stolen from him, he shall make restitution to its owner. 13 If it is torn by beasts, let him bring it as evidence. He shall not make restitution for what has been torn. 14 “If a man borrows anything of his neighbor, and it is injured or dies, the owner not being with it, he shall make full restitution. 15 If the owner was with it, he shall not make restitution; if it was hired, it came for its hiring fee.

This offers an important nuance to the law, a nuance that offered some protection to the one in whose care the property of another was placed but who did not steal the property or damage it willfully or even knowingly. There is also a strong note of divine arbitration in this text. For instance, consider verse 9:

9 For every breach of trust, whether it is for an ox, for a donkey, for a sheep, for a cloak, or for any kind of lost thing, of which one says, ‘This is it,’ the case of both parties shall come before God. The one whom God condemns shall pay double to his neighbor.

Two things should be said about this. First, the need to appeal to the Lord suggests that many situations are not terribly clear-cut regarding who exactly is at fault and what the penalty should be. This should be kept in mind. There are situations the reality of which only God knows and only God can decide. Furthermore, these situations would presumably need the mediation of the people of God unless God makes it clear directly to the hearts and minds of the parties what the reality is. In the age of the Church, this will likely result in something like the mediation of wise and trusted Christian friends who are capable of being objective and judicious in disputes between members. This is what Paul called for in 1 Corinthians 6.

1 When one of you has a grievance against another, does he dare go to law before the unrighteous instead of the saints? 2 Or do you not know that the saints will judge the world? And if the world is to be judged by you, are you incompetent to try trivial cases? 3 Do you not know that we are to judge angels? How much more, then, matters pertaining to this life! 4 So if you have such cases, why do you lay them before those who have no standing in the church? 5 I say this to your shame. Can it be that there is no one among you wise enough to settle a dispute between the brothers, 6 but brother goes to law against brother, and that before unbelievers? 7 To have lawsuits at all with one another is already a defeat for you. Why not rather suffer wrong? Why not rather be defrauded? 8 But you yourselves wrong and defraud—even your own brothers!

The Lord may yet speak directly in such matters, but it would seem that He normally speaks through the Church. In our highly individualistic day in which ecclesiology is weakened by a heightened since of isolation, humanity, and detachment from the community of God, such an appeal to and acceptance of the wisdom of our brothers and sisters in Christ will feel odd at first, but it may just be that we are missing a great blessing by not asking trusted followers of Jesus to help us in our disputes (with other Christians) over property and the like.

Within the church, we should seek to live honestly and uprightly with one another, offering restitution when we have wronged another, yet striving to show Christ-like compassion and Kingdom priorities when we are the one who is wronged.

As with all of these laws, we must ask how we should follow them in a day in which the cultural particulars are in many ways quite different than the particulars of ancient Israel. To begin with, we should perhaps question whether or not our day really is all that different. After all, disputes concerning property are as old as humanity itself, and in our materialistic age, when we have more than any people before us have ever had, they are very common indeed.

Concerning the basic principle of restitution, we see it honored in the New Testament. Consider the story of Zacchaeus in Luke 19.

1 He entered Jericho and was passing through. 2 And behold, there was a man named Zacchaeus. He was a chief tax collector and was rich. 3 And he was seeking to see who Jesus was, but on account of the crowd he could not, because he was small in stature. 4 So he ran on ahead and climbed up into a sycamore tree to see him, for he was about to pass that way. 5 And when Jesus came to the place, he looked up and said to him, “Zacchaeus, hurry and come down, for I must stay at your house today.” 6 So he hurried and came down and received him joyfully. 7 And when they saw it, they all grumbled, “He has gone in to be the guest of a man who is a sinner.” 8 And Zacchaeus stood and said to the Lord, “Behold, Lord, the half of my goods I give to the poor. And if I have defrauded anyone of anything, I restore it fourfold.” 9 And Jesus said to him, “Today salvation has come to this house, since he also is a son of Abraham. 10 For the Son of Man came to seek and to save the lost.”

Zacchaeus’ statement that he would give half his goods to the poor and “fourfold” to anyone who he defrauded shows a basic resonance with the principles of Old Testament law. The difference, of course, is that Zacchaeus was standing before Jesus. This means he offered restitution freely, gladly, and out of a since of gratitude for the greater gift he had been giving. For Zacchaeus, this was not about “obeying the law,” this was about honoring Jesus Christ and living the new life to which he had been called in Christ.

So should it ever be with us. We read these laws with gracious hearts because they reveal to us the heart of God. In Jesus, we find a motivation than transcends mere fear (though fear yet has its place). In Jesus we find the motivation of love. We refuse to steal because we love God and love our neighbor. We refuse to defraud because to do so dishonors the great gift that has been given to us through Christ.

Yet there is another truth about the Christian’s approach to property and theft and restitution, and it is a painful but necessary truth. It is this: for the Christian, getting back what was taken is no longer the greatest good or the highest priority. Desiring as we should for all men to come to Jesus, exacting justice upon a thief and reclaiming what was ours can no longer be the end-all-be-all for us. Instead, the salvation of the thief must matter to us more. I think this helps us understand what is happening in Matthew 5.

38 “You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ 39 But I say to you, Do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. 40 And if anyone would sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well. 41 And if anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. 42 Give to the one who begs from you, and do not refuse the one who would borrow from you.

What we see here is Jesus (a) acknowledging that certain things are ours (“your tunic…your cloak”) but (b) asking us to prize and value something more than what we own: our own souls and the soul of the one who is taking from us. He is asking us to value our own souls by not allowing ourselves to be so bound to temporal goods that we cannot simply let them go. He is asking us to value the soul of the one taking from us by stepping outside of the arena of pure justice and instead infusing the situation with the grace that forgiveness brings.

In truth, there is one thing that goes much further than prison or a fine in rehabilitating the heart of a thief, and that is forgiveness and grace. That is a scary prospect for us. After all, we want to get back that which was stolen. But the point is this: would you have greater joy in regaining a temporal good or in gaining a brother or sister in Christ? In James 5, James wrote:

19 My brothers, if anyone among you wanders from the truth and someone brings him back, 20 let him know that whoever brings back a sinner from his wandering will save his soul from death and will cover a multitude of sins.

In Matthew 18, Jesus put it like this:

15 If your brother sins against you, go and tell him his fault, between you and him alone. If he listens to you, you have gained your brother.

“Gaining your brother” and “bringing back a sinner from his wandering” should be the greatest goal of the follow of Jesus. What if your simply giving the item to the thief would move him to repentance? What if your refusing to press charges would show him the better way of grace?

To do so is to risk, but not really. If the thief does not repent, we are left with the good pleasure of the Father who sees us trying to bless and love our enemies. If the thief does repent, we receive the good pleasure of the Father and win a brother or sister as well.

In 2007, WMC-TV in Memphis ran a report about a ninety-two year old woman from Dyersburg, Tennessee, who got into her car in a Wal-Mart parking lot only to have an armed robber get into her car as well and demand all of her money. She refused, informing the man that were he to shoot her she would immediately go to heaven with Jesus whereas he would go to hell! She then shared the gospel with the man for ten minutes, at the conclusion of which, the robber began to cry, told her he would not rob her, informed her that he needed to go pray, and then kissed her on the cheek. In turn, she freely gave him all the money she had, which was ten dollars.[4]

To be sure, such courage and bold witnessing will not always be met with tears and repentance. It may very well be met with violence and even death. Even so, this lady’s amazing actions stand as a stark reminder that we should value the thief’s soul more than we value either our property or our lives. Perhaps the example of this dear lady can remind us of this fact.

Church, there are things more important than property.

Surely Jesus has taught us that? Let us choose the way that is better than vengeance or a blind demand for justice at any and all costs.

[1] Terence E. Fretheim, Exodus. Interpretation (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), p.201-207.

[2] William H.C. Propp, Exodus 19-40. The Anchor Bible. Vol.2A. (New York, NY: Doubleday, 2006), p.240-241.

[3] Joseph T. Lienhard, ed., Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture. Old Testament, Vol.III (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2001), p.114.

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fDmp967UMds

Pingback: Exodus | Walking Together Ministries