I had somehow missed Andrea Arnold’s 2011 “Wuthering Heights.” The book is one of my favorites. I do so love the Bronte darkness over the Austen cheer (though I certainly appreciate Jane Austen as well) and, as a result, I greatly appreciate good film adaptations of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights in particular.

I had somehow missed Andrea Arnold’s 2011 “Wuthering Heights.” The book is one of my favorites. I do so love the Bronte darkness over the Austen cheer (though I certainly appreciate Jane Austen as well) and, as a result, I greatly appreciate good film adaptations of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights in particular.

This particular adaptation is unique for three reasons. First, Heathcliff is black, a former slave. Truthfully, against my initial skepticism, I thought this worked. In the book, he is described as a dark-skinned gypsy, thus, his being black and a former slave fits the exotic foreignness that the book sought to project on his character. Secondly, the language and some of the scenes will go down, as far as I know, as more coarse than the language and scenes of the previous film adaptations of the book. Some of this struck me as fitting the book’s tone and temperament and some of it struck me as unnecessary, and, in one instance, gratuitous.

The third unique factor is what struck me as most intriguing. It also explains why fan reactions to the movie tend to be some shade of either abhorrence or adulation. I am speaking of the film’s heavy reliance on atmosphere, its elevation of nature (wind, in particular) to the status of a character, its bleak vision, and its sparse dialogue and brooding pace. In terms of pace, think Philip Gröning’s 2005 documentary on the Carthusians monks, “Into Great Silence.” I’m being serious here. A consideration of the trailers for the two films will show what I mean.

The camera lingers long over scenes. There is no music in the film until the very end (and the choice of song was, in my opinion, a misstep). It is a very different experience watching this movie. Long shots of moths fluttering at windows, bugs crawling over the ground, fruit, the moors, dogs, the sky, birds, the characters staring into the distance or each other’s faces in silence, etc. dominate the film. In particular, the wind is given prominence, rightly so, and becomes a character in its own right, particularly in the grueling scene in which Heathcliff attempts to pry open Catherine’s coffin.

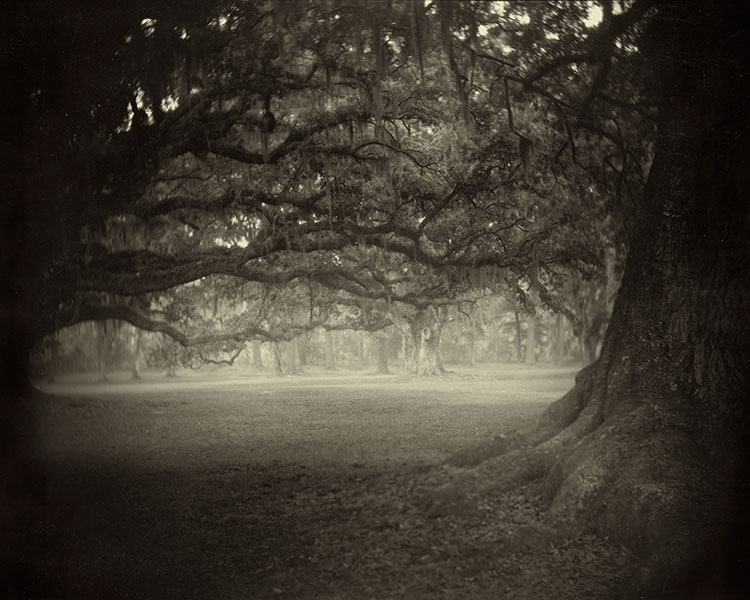

Furthermore, the imagery is grey, grey, grey. It, too, highlights the tension, the angst, and the tragedy of the story of Heathcliff and Catherine. Here I could not help but think of Sally Mann’s enthralling “Deep South” images. Just compare the images:

Deep South

Wuthering Heights stills:

The overall effect is ominous, Gothic, and profoundly contemplative. I kept thinking of my earlier bouts with Seasonal Affective Disorder and how I simply would not have survived the moors at a certain time in my life.

Now, however, I find this whole ethos to be powerful and beautiful. As such, I greatly appreciated the film. One will either like this approach or hate it. It forces a kind of stillness upon the viewer, and demands an emotional and psychological investment in the pathos and sadness of the story itself.

I can imagine that the film is not for everyone. I can even see why many did not like it. For me, it fit the book perfectly in its sparse, bleak, strangely beautiful, and sometimes brutal depiction of a doomed relationship and of human nature in general.